Download PDF →

MAJ Jon Page served in various positions including assignments in the 10th Mountain Division, the 1st Cavalry Division, and the U.S. Army Headquarters. He is currently assigned to the Air Land Sea Application Center.

On March 6, 2020, the Office of the Under Secretary for Defense and Intelligence published Department of Defense Instruction (DODI) 5200.48, Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI). The publication of initial standards and implementation represented a culmination of executive branch efforts begun in November of 2010. According to Executive Order (EO) 13556, the President of the United States recognized that “executive departments and agencies employ ad hoc, agency-specific policies, procedures, and markings to safeguard and control… information that involves privacy, security, proprietary business interests, and law enforcement investigations.”[1] EO 13556 represented the efforts of the Obama administration to standardize controls for unclassified information in the interests of both protection and transparency.

Yet, since March 2020, implementation of DODI 5200.48 has not been smooth or clear for the individual Services, the Joint Staff, or the Department of Defense as a whole. One of the effects of the implementation has been the creation of a potential barrier to information sharing with partners and allies. Use of CUI involves specified guidelines for its electronic protection which may create unnecessary barriers to efficient disclosure and negative consequences to partner trust. The Joint Force must address the challenges created by poor implementation of controlled unclassified information (CUI) procedures to ensure multinational information flow is not negatively impacted in the future. This article will offer some background on classification in general, including the negative effects of over-classification. It will describe these effects on U.S. partners and allies. From there, it will review the framework within CUI policy and its effects on foreign disclosure. Finally, it will provide recommendations for organizations to better align U.S. CUI policy in the interests of greater transparency to achieve shared goals with our partners.[2]

In 2017, roughly four million Americans holding security clearances generated fifty million classified documents. Officials including former director of the National Security Agency, Michael Hayden, have complained these number represent systemic over-classification within the executive branch. In 1971, Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart remarked in a court opinion, “When everything is classified, then nothing is classified, and the system becomes one to be disregarded by the cynical or the careless, to be manipulated by those intent on self-protection or self-promotion.” The current administration of classification policies might have a hand in over-classification. Mistakes in under-classifying are clear, carrying administrative and possible legal penalties as well as threatening national security. Over-classifying carry no such penalties. Greater secrecy can also create barriers to effective and efficient information sharing, as demonstrated in the 9/11 Commission Report. The terrorist attack on 9/11 might have been prevented with greater information sharing, thus informing decision-making or making the public aware to greater dangers.[3]

These are problems with classified documents and information. Part of the reason for the issuance of EO 13556 was in response to the adverse effects of over-classification on unclassified information. It sought to standardize the various executive branch caveats for unclassified information, such as defense use of ‘For Official Use Only’ and police force use of ‘Law Enforcement Sensitive.’ Not only did each caveat come with its own marking criteria, often poorly understood by other organizations, it created a hodge-podge of criteria for use, instructions for electronic sharing and storing, and penalty for misuse of criteria and instruction. Documents often were not interrogated for the rationale behind their caveats on unclassified documents resulted in greater use of the caveats. As the caveats were brought under encryption requirements within email use and storing, not only were they withheld from public oversight in some instances, but they also became restricted from our international allies and partners. EO 13556 was meant to address these concerns. Yet, the defense department instructions for implementing the executive order, DODI 5200.48, has created confusion and initially has not eliminated the problems with unclassified caveat usage.[4]

Under the new framework, unclassified information exists in two forms. The first form is simple unclassified information without caveats or controls. This unclassified information requires no specific safeguarding related to its storage and transmission in print or electronic media. The second form is unclassified information with specific controls,

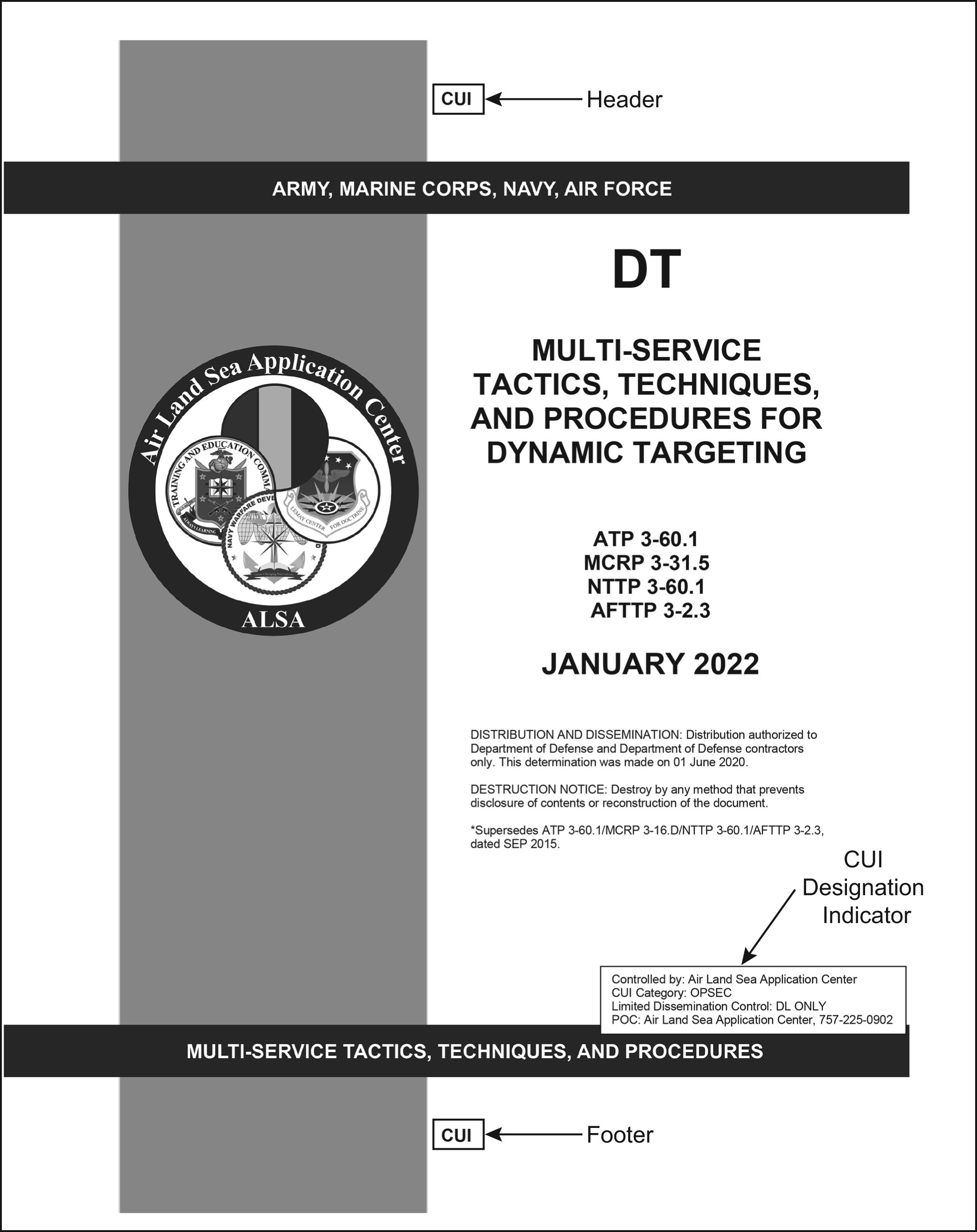

controlled unclassified information. As we have discussed, the DOD has published a framework for identification, storage, and dissemination of CUI. First, DODI 5200.48 has created a DOD CUI Registry to align all the disparate categories under which DOD was previously caveating unclassified information (such as FOUO- For Official Use Only). Second, the DODI instituted specific marking criteria for CUI, including a specified five-line designation indicator identifying the rational, controls, and controlling agency. Figure 1 shows an example of this designation indicator. This designation indicator is meant to address the problem of not being able to identify the origination of controls as many organizations do not require Security Classification Guidance use in previous caveats for unclassified information (e.g., FOUO).

[5]

Figure 1 - Example of CUI markings including Designation Indicator[6]

Figure 1 - Example of CUI markings including Designation Indicator[6]

The Intelligence and National Security Alliance (INSA) has identified several problems with the implementation of CUI policy within the DOD and Intelligence Community. Specifically, they describe the implementation as “complex, confusing, and costly.” The complexity issue should be acknowledged. Not only does the CUI program identify 20 groupings and 125 categories for identifying unclassified information as requiring additional controls, but agencies are also left to implement CUI program independently of each other, creating complex and confusing rules for each agency. For instance, the Department of Defense follows DODI 5200.48 as its foundational document for the CUI program. This document identifies controls to be used, such as caveats including no foreign dissemination (NOFORN), REL TO (Releasable To), and other caveats. Additionally, DODI 5200.48 identifies that previously marked controlled unclassified information, such as doctrine publications marked under distribution statements and documents identify as FOUO, should be reviewed, and updated with the new markings.

This complexity and confusion compounds when factoring in foreign disclosure and release of information to partners and allies. Foreign disclosure officers are typically trained and given authority to conduct review of classified information for release to partners and allies. Typically, they are trained to review security classification guidelines (SCG) and coordinate with classification authorities (as identified in cover statements and sourcing material) to determine redactions and release to partners and allies in a timely fashion. The CUI program has created more complexity for that role. Now, disclosure officers have an entire new set of unclassified caveats to review and in the implementation phase of the program, confusing criteria for identification (CUI documents do not currently require portion marking), coordination (many CUI documents come without the specified cover information – see Figure 1), and review (security classification guidelines are being updated concurrently with the implementation of CUI). Finally, CUI program implementation requires encryption of CUI documents and information, resulting in the inability to rapidly transmit unclassified information to partners and allies, unless they hold a U.S. generated email or other U.S. digital account.[7]

So, what can organizations do to ensure information sharing with partners and allies is not interrupted by imperfect implementation of the CUI program? There are three specific recommendations to implement, which may be instituted at organizations with more than 100 personnel. First, organizations should aggressively implement the use of the specified cover CUI designation indicators for their CUI marked documents. Second, operations security (OPSEC) officers should be placed in charge of releasing and updating controls for OPSEC identified non-portion marked CUI documents. Finally, OPSEC officers and foreign disclosure officers should retain freedom to update CUI controls for improperly marked documents, including those without adequate cover information.

All CUI marked documents in the DOD require cover designation indicators. Yet, in the implementation phase of the CUI program, many documents simply do not have these cover statements. Organizations identifying unclassified information should aggressively review and place these indicators. This ensures that the proper rational has been used in identifying why a document requires controls, identifies those controls, and provides the agency to contact with questions about those controls. Ensuring all that information properly exists within a cover designation indicator will ensure efficiency in disclosure review and release.

A clear CUI category is OPSEC and many legacy FOUO documents and newly identified CUI at operational organizations are identified for safeguarding due to the need to protect information for OPSEC purposes. The proper reviewer of documents identified as such should reside with the organizational OPSEC officer until the CUI program matures. These OPSEC officers will be better able to identify needed redactions for information identified for release from their organizations and will also be able to understand timing and questions to ask of other organizations in determining release criteria for derivatively received CUI documents. They should retain freedom to add additional controls to ensure timely release of OPSEC marked documents to allies and partners.

Documents marked CUI with appropriate REL TO identification should be available for transmit outside of encrypted channels. Using OPSEC officers in this role will also allow foreign disclosure officers to focus on their own procedures in classified reviews and free time for the foreign disclosure officers to review other CUI categorized documents. At this stage of CUI implementation, many documents will come into organizations without proper cover designation indicators. At this point, OPSEC and foreign disclosure officers should retain the freedom to either add a cover designation following review or add additional caveats in the interest of expedited sharing to partners and allies through the application of REL TO statements.

While CUI implementation has been in development for more than a decade, the actual practice has resulted in complexity, confusion, and cost. Much of that cost has been in the form of reduced efficiency and effectiveness in transmitting CUI marked documents to our partners and allies. Organizations within the Joint Force may best address the challenges in poor implementation by aggressively ensuring cover designation indicator use, allowing their OPSEC officers to review and release OPSEC identified CUI, and retaining the freedom to release improperly marked CUI as mission demands require. Organizations that follow these recommendations may ensure that multinational information flow to allies and partners does not suffer negative impacts to information sharing.

Endnotes

[1] Office of the President of the United States. Executive Order 13556, “Controlled Unclassified Information.” United States of America, 2010.

[2] Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security. DOD Instruction 5200.48, “Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI).” U.S. Department of Defense, 2020.

[3] Hathaway, Oona. “Keeping the Wrong Secrets.” Foreign Affairs 101, no. 1 (2022): https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/united-states/2021-12-07/hacking-cybersecurity-keeping-wrong-secrets

[4] Intelligence and National Security Alliance (INSA). “Complex, Confusing, and Costly: Challenges Implementing the Government’s Controlled Unclassified Information Program.” INSA Security Policy Reform Council, 2021.

[5] Office of the Under Secretary of Defense for Intelligence and Security. DOD Instruction 5200.48, “Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI).” U.S. Department of Defense, 2020.

[6] The Air Land Sea Application Center. Multi-Service Tactics, Techniques, and Procedures for Dynamic Targeting. Air Land Sea Application Center, 2022. https://www.alsa.mil/mttps/dt/

[7] Intelligence and National Security Alliance (INSA). “Complex, Confusing, and Costly: Challenges Implementing the Government’s Controlled Unclassified Information Program.” INSA Security Policy Reform Council, 2021.